By Jason O’Toole

Greenwich Village became the capital of Bohemian culture in the 19th Century when the avant-garde and the counterculture availed themselves of cheap rental space to meet, create and perform. Walt Whitman and Marcel Duchamp would call it home as would the writers knowns as The Beat Generation. Their Beatnik copycats followed them to the Village and swarmed their cafes and jazz clubs. In the Village Vanguard, Village Gate, and The Blue Note, jazz gave way to Folk and Rock. Bob Dylan and Jimi Hendrix played to their first audiences on their stages.

Today, these images of The Village live mostly in the memories of those who were there, and the imaginations of idealists. Would-be hipsters of today make a pilgrimage to this site only to find it resembles any other neighborhood where high rents have chased away all but the very wealthy. Perhaps they’d have better spent their time staying in the suburbs reading the poems and stories of those who documented the phenomena that was the Village.

In the years after WWII, Chandler Brossard documented the Village and the rise of the hipster. He was a grade school dropout whose talent for writing earned him a spot as a reporter with the Washington Post at age 17. In conversation with Dr. Iris Brossard, a poet and retired neurologist, she recalled her father saying that he “thought education was bull” following his own path with the help of his older brother Vincent. She noted that her father loved to read and was born to write, finding his own unique American voice along the way. He devoured the works of German Realist Theodor Strom, Austrian Modernist Hermann Broch, and militarist and “Storm of Steel” author Ernest Jünger. He absorbed the gritty stories of the plain speaking, chronicler of the French working-class Louis-Ferdinand Céline and the Christian mysticism of Fyodor Dostoyevsky.

The backstreets of Washington, D.C. were the setting for Brossard’s novel The Bold Saboteurs, the story of a young teen, loosely based on himself who falls under the sway of a gang of thieves, hustlers, and male prostitutes. Yogi is something of a more foul-mouthed and felonious Holden Caufield whose surreal hallucinations weave in and out of the otherwise matter-of-fact narrative. Yogi’s ham-fisted theft of cheap jewelry from a fellow thief’s girlfriend makes him feel like the king of the neighborhood until he is fingered as the culprit. One of the most striking passages in the novel depicts Yogi’s visions, at a most inopportune time being booked by the police. Here, Yogi hallucinates the return of his absent, alcoholic father:

“Now I was in an absolutely quiet corner of the station house. Here I experienced a strange tidal sensation all around me and inside myself. It was very emotional and a little sexual. Before me was my father, very bloated and a little dreamy looking and dressed in what resembled a policeman’s uniform. He smiled vastly at me but I did not smile back. My father reminded me of some giant fish, a whale or porpoise, that had been stranded on the beach. He was murmuring vast, oceanic nothings to a small man in a black raincoat who was pretending to write it all down in a very official-looking black notebook.”

The Bold Saboteurs (Farrar, Straus, 1952)

At 19 Brossard moved to NYC where he wrote for The New Yorker and started writing short stories. The carnal, street-level view of grifters, prostitutes and other sundry outcasts stood in stark contrast to the values of his Idaho Mormon roots. His unfailing work ethic would make him a standout in the publishing world. In the Village, Brossard rubbed shoulders with the Jewish community. The Mormons believe they were descended from the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel and Brossard found a special affinity for them. Brossard also discovered the highbrow society and Bohemian counterculture that thrived in Mid Century Manhattan and navigated through both milieus.

Though lumped in with The Beats such as Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs, Brossard did not care for the label, nor for the “bad writing,” drug abuse, and overall moral degeneracy he perceived. Although he was impressed with Burroughs’s first novel, Junky which he described as “a classic naturalistic, sort of philosophic work” and enjoyed parts of Naked Lunch, he held the movement in contempt. Though outwardly a Bohemian writer, Brossard was inwardly a rugged, Rocky Mountain Mormon. Brossard was by this time so successful in his career that he had two apartments, one in a building shared by Burroughs as well as sculptor Claes Oldenberg and Burrough’s friend David Kammerer. Kammerer became infamous for aggressively stalking original Beat, Lucien Carr, a member of the Scout Troop he led back in St. Louis until ultimately falling to Carr’s Boy Scout knife in a final moment of poetic justice.

To escape the perpetual madness of the Village, Brossard kept another apartment on the more fashionable and respectable West Side. Iris remembers her father declaring “I was never one of the Beats. That was all a media invention anyway. I hated those people. I thought they were scum.”

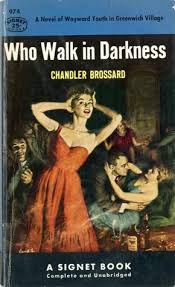

Brossard’s first novel was more appreciated in France where it was read in the context of the New Wave movement of the 50s and is remembered as the first American Existential novel. Who Walk in Darkness, (the title, a reference to Isaiah 9:2) was discovered by the influential French poet and critic Raymond Queneau and published by Gallimard to critical acclaim overseas. The NYC independent publisher New Directions picked up the novel, but not without conflict and controversy. New Directions introduced Americans to the early work of Ezra Pound, Thomas Merton, Dylan Thomas and Vladmir Nabakov. Brossard had every reason to expect that he would enjoy similar renown.

The main protagonist of Who Walk in Darkness was based on Anatole Broyard, an important figure in the New York literati. An African-American who passed for white, Broyard used this to his advantage professionally as well as socially. Iris describes the character of Henry Porter as “a metaphor for a morally bereft person.” Iris reported that one likely version of events is that the poet Delmore Schwartz was not in the loop when the book was green lighted “and as revenge, he passed it on to Anatole.”

Broyard was originally from New Orleans and some sources insisted that he enlisted in the segregated Army as a white man, rising through the ranks to become Captain over a black battalion. After the Army, Broyard left behind a wife and child, conceived in a failed effort to avoid military service. He found his way to Greenwich Village and used the G.I. Bill to enroll in evening classes at The New School for Social Research. He used his Army savings to open a small, specialty bookstore famous for its discerning collection.

Broyard told the few who knew the truth, that his ruse was based on the understandable desire to be viewed as a writer, not a black writer. Nonetheless, his earliest non-fiction pieces centered on the black experience, including the peculiarities of those who chose to pass themselves off as white. A short story about his father’s death attracted so much acclaim from Norman Mailer and other literati, that he was awarded the staggeringly huge advance of twenty thousand dollars for his first novel.

Rumors swirled around Broyard: did his acute understanding of black culture emerge from close study or, was he in fact of such extraction? Broyard dodged this question, claiming he had “island influences” and vehemently denied the truth. He even kept this secret from his own children and was known to express caustic views of blacks, rivaling the prejudices of the rich Connecticut WASPs whose acceptance he sought. Brossard found his friend’s predicament irresistible and wrote him into Who Walk in Darkness as the shameless opportunist “Henry Porter.”

Broyard saw his thinly veiled and harsh (if accurate) portrayal as a betrayal by a trusted colleague and threatened a law suit if the character were not rewritten. To placate him, the New Directions edition features a protagonist who is described not as hiding his blackness, but instead an “illegitimate.” Dr. Iris Brossard recalls her father being demoralized by the lack of commercial or critical success and feeling that this forced change completely ruined the central metaphor of his novel.

Broyard went on to become a powerful New York Times book critic. As an elite gatekeeper for arts and letters, he could ruin a promising career with a single cruel review. “He decided to destroy Dad’s book, Wake Up We’re Almost There just for fun,” recalls Iris. His brutal review in the Sunday Times was the last straw for Brossard and many other writers. Anatole had by that point earned a reputation as someone who would unswervingly stab old friends in the back. The backlash was swift and severe, and the one thing he feared most, that his blackness would be exposed, was shouted in everywhere. Today if Broyard is remembered for anything, it is for desperately pretending to be someone else.

Iris recalls that her father took an editing job at LOOK, the defunct bi-weekly remembered for the historic photo-journalism of James Karales, who covered the Civil Rights marches, and the noir, off-beat slice-of-life shots of a very young Stanley Kubrick. Iris recounts a story of LOOK in the 60s, doing a feature on the Folk scene. Bob Dylan and Joan Baez showed up at the LOOK offices and as they were “fans of my dad’s books and asked to meet him. He came down, in his three-piece Brooks Brothers suit, clearly not what they expected…I think they kind of stared at each other.”

Run off from LOOK for his Bohemian political views, out of step with the conservative, all-American image that LOOK wanted to project, Brossard accepted a series of university teaching jobs, despite having no formal education. In those days, experience and talent counted more than fancy diplomas, and Brossard taught in some top programs (including my own alma mater, The New School).

Brossard would go on to write or edit 17 books, many now out of print. His fiction is as good as, or better than his impressive influences, and his honest and direct storytelling still has the power to resonate with readers today. While you’re searching for literary treasures in the used book stores and bargain bins, one would do well to keep any eye out for the overlooked, ground-breaking novels of Chandler Brossard.

Sources:

Henry Louis Gates, Jr., “White Like Me” The New Yorker. published June 17, 1996 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1996/06/17/white-like-me

The Review of Contemporary Fiction,” Spring 1987, Vol. 7.1

Chandler Brossard: Who Walk in Darkness (1952), The Bold Saboteurs (Farrar, Straus, 1952), Wake Up, We’re Almost There (R.W. Baron, 1971).

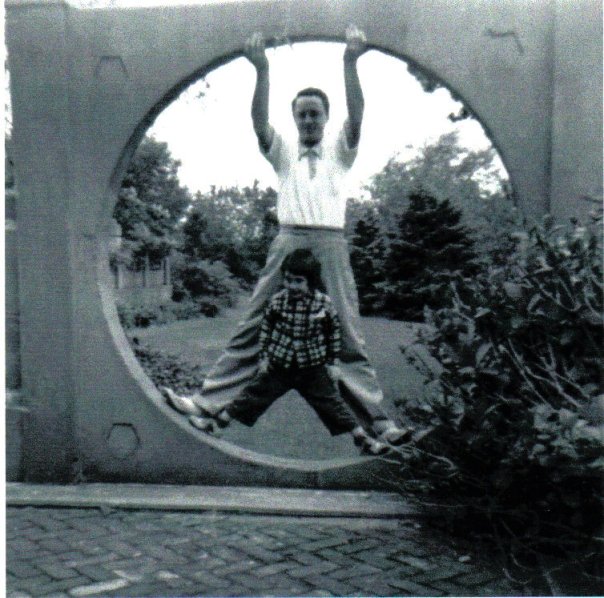

Special thanks to Dr. Iris Brossard for the interview and family photographs.